Generally, community energy projects have been about coming together to install a generation project on a community-owned building.

To get to net zero, we need to go much further than that. The way we heat our buildings is critical to reducing carbon emissions, and towns and cities need to find solutions that address all of our ageing housing stock.

This CES webinar on 18 May heard from groups, businesses and communities who have looked at tackling carbon on a street-by-street approach.

Street-by-Street Ground Source Heat Pumps

Lisa Treseder of Kensa – a Cornish heat pump manufacturer, has been attempting to do just that.

Lisa set out the sheer scale of the challenge we face with decarbonising heating, one of the reasons being we’re just very comfortable with gas, covering 85% of homes as it does, and 1.7m new gas boilers still being installed each year. It takes an awful lot to change people’s behaviour, not to mention the infrastructure behind it.

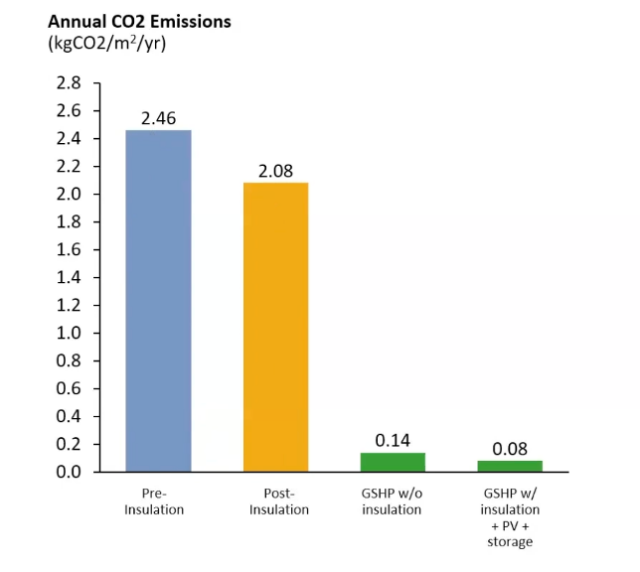

But, if the question is net zero, the answer is heat pumps – as the diagram below shows – the blue and yellow bars representing CO2 emissions from gas boilers, the right two with ground source heat pumps:

However, at the rate we are installing heat pumps currently – around 50 thousand per year – we will reach net zero 600 years from now.

Kensa’s Heat the Streets project sought to replicate the familiar set up of the gas grid with ground source heat pumps – based on standing charges, plus metered energy use. Due to the funding it received, the public would not have to fit the bill for installation.

The principle behind the project, that Kensa owns the infrastructure, people pay their bills – is theoretically easily replicable everywhere – the idea was to set up an evidence base so others copy it. The more people do, the more trust in the solution.

Think of it as a demonstration of what is possible – changing the ownership model, reducing the barrier of upfront cost to people. The advice to other similar projects was not to try to fix everything in one go and over-stretch, but instead pick the challenges you can overcome in a demonstration project.

A lot of community engagement is needed for retrofit, to get people on board, and to ensure they don’t block its progress. To this end, Kensa used a sales funnel approach to its communications, from raising awareness to building interest. Crucially it also had a dedicated resident liaison officer who offered aftercare and support and is still doing so.

Using the same framework, it then simply choose the street with most interest to begin the project first. Some would be connected with heat pumps straight away, while the array set up in the street would ensure others had the option of joining in future when their current heating systems broke down, “one of the more exciting things about this project.”

The result was apparently a world-first for in-road retrofit of a ground array – 100 heat pumps installed on five sites, and overall a 70% carbon emission reduction. The project provides a model for off-gas rural villages. Though clearly cost and price perception are two major areas that still need to be addressed in any follow up.

Approaches to Retrofit

Switching to a fabric-first approach, next up, Jonathan Atkinson from Carbon Co-op explained its street-by-street approaches to retrofit, or an area-based approach:

This is the creation of a standard offer to anyone who lives in an area. The concept coming from a 2010 Erbed report called Community Green Deal, which established the idea of a community-led intermediary sitting between householders, and others e.g. investors, local authorities etc – to develop a standardised approach to retrofit.

It benefits from a partnership approach, central procurement and potentially a mixture of funding. It can also offer the benefit of scale and speed, at a time this is needed.

In phase 1 of delivering this approach in South Manchester, Carbon Co-op’s approach was to deliver external wall insulation, improved windows, air tightness plus ventilation. All measures incidentally, which would prepare homes well for heat pump installation in future, without excessive demands on the grid that might happen otherwise.

In terms of the funding offer, this is a unique deal – Carbon Coop can grant money itself based on previous funding. Up to £25k funding is also available via the council, which goes as a charge on the house – no interest or upfront fee – the money is discharged when the householder sells the property. Many councils have this option, but have forgotten it or don’t use it. It sits as an asset on their books, so works well for them too versus direct revenue lending.

GUCE

Sarah Burgess from Grand Union Community Energy (GUCE) explained the story behind the group’s investigations into pulling heat from the local canal. Initially, the idea was this might heat 12 houses in Kings Langley initially – one street effectively. However, they discovered the canal had dried up once in its history, raising questions. Its temperature range also varied from 4-14 degrees, made it “slightly risky and probably not worth it.”

However, the village had its energy requirements measured in the process by a third party, and what they discovered was that in the past an old Ovaltine factory – now flats – had had boreholes drilled into the aquifer – which had the potential to heat the whole village. Most of these bore holes were directly under the factory itself so inaccessible – but there’s a good chance the aquifer may also be reachable from the other side of the village. GUCE is currently in the process of drumming up community involvement to bring this idea fully to life.

With a lower potential buy-in for individual households than individual heatpumps, it is hoped that the project will be able to decarbonise heating and provide energy security across the village, without leaving anyone out.